Five reasons why re-padding a bassoon is so complicated

May 22nd, 2020

Five reasons why re-padding a bassoon is so complicated

Article Author: Oliver Ludlow, In-House-Bassoon Specialist and Director at Double Reed Ltd.

Five reasons why re-padding a bassoon is so complicated

1. Unusually complex keywork

Modern bassoons have one of the widest ranges in the orchestra, from B♭1 (below the bass staff) and go up to about G5 (above the treble staff). Like most wind instruments, these notes sound using toneholes and vents drilled into the bore, each needing to be placed very precisely up and down the instrument.

Plenty of instruments have mechanisms which allow the player to open and close all of its toneholes, but with the bassoon this is true in the extreme. Most of the bassoon’s toneholes and vents are unreachable due to its sheer size, and so long and complex pieces of metalwork, incorporating levers of a bewildering variety (known collectively as keywork), are used to connect the fingers of the bassoonist to the toneholes or vents needed to play a particular note. In total, the average bassoon has 40 pieces of keywork, which if lined up end to end would stretch almost 5 metres!

Photograph: Bassoon keys disassembled

Over years of playing, keywork can become loose or bent, causing pads to seat imprecisely. A specialist bassoon repairer will be able to fix these issues, but must do so without damaging the keywork or the plating on top - bassoon keys can snap relatively easily, and the plating can be prone to cracking if pressure is applied carelessly.

Because of its unusual complexity, regulating the keywork precisely takes a high degree of accuracy. Each component of the series of levers has to be carefully adjusted to ensure that the pad makes a firm seal with the tonehole.

Spring tensions also need to be fine-tuned - the springs need to be strong enough so that pads don’t blow open, but not so strong that the instrument is difficult to play.

2. Pads, corks and felts

Regulating a bassoon’s keywork is further complicated by the fact that the distance of an open pad from its tonehole will affect the tuning of that note. A bassoon repairer will need to adjust the thickness of roughly 45 corks and felts on the bassoon’s keys to obtain the correct regulation, and carefully balance their thickness against how it affects the rest of the mechanism attached to that key.

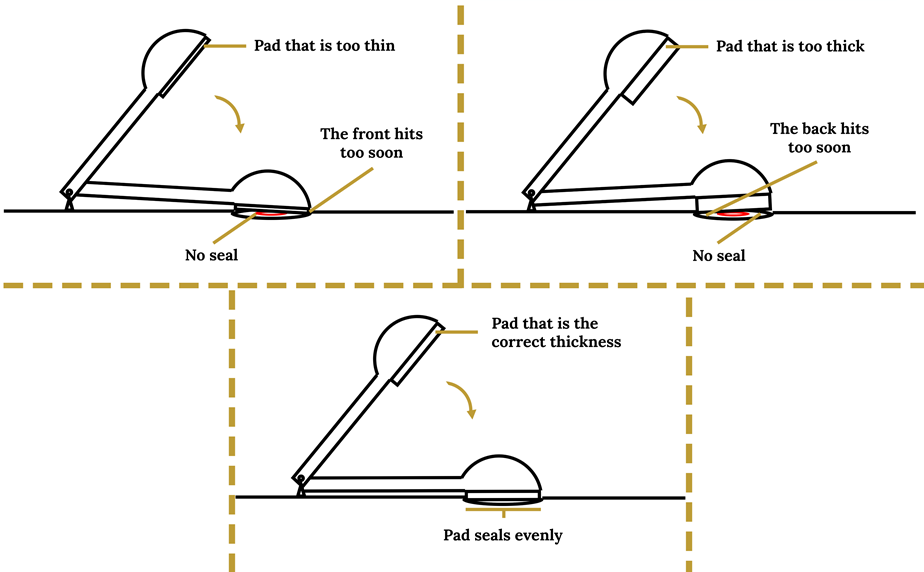

The size and thickness of the pads themselves also present complications when re-padding a bassoon. There are countless thicknesses to choose from for every pad, and the correct one can vary from bassoon to bassoon and from key to key. Selecting the wrong thickness can cause the pad to leak, whether it is too thick or too thin (see diagram).

Diagram: Bassoon pad thicknesses

This problem is of particular note because over time the pad will bed in, so what seems like the correct thickness of pad when first fitted will not necessarily be the correct thickness later on. The bassoon repairer learns over time how much to compensate for this effect by using differing pad thicknesses for different keys.

The pad can be angled to compensate if it is hitting at a slight angle and leaking, but this can only be done a small amount, as pad cups are quite shallow so the pad has little scope for adjustment. A pad that is angled too much is also likely to start leaking over time because of uneven pressure from the pad cup.

3. Oblique tonehole angles

The tonehole faces on many woodwind instruments are domed, allowing the rim of the tone hole to protrude above the rest of the face. This reduces the risk of leaks once the pad goes down. If the face was flat, the pressure from the pad would be spread across a larger surface area and thus be weakened, but with a dome, the pressure is applied exactly where it needs to be – at the rim of the tonehole.

Photograph: Domed bassoon tonehole

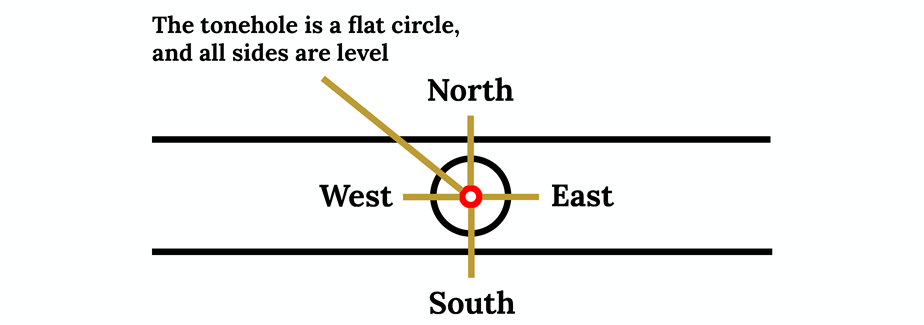

The domed tonehole face doesn’t cause too many complications for most woodwind instruments, because they are mostly drilled at right angles to the direction of the bore (i.e. vertically into the instrument). This results in tonehole rims which are level, flat circles, and flat pads can easily cover them.

Diagram: A woodwind instrument with a tonehole drilled at a 90 degree angle with the bore

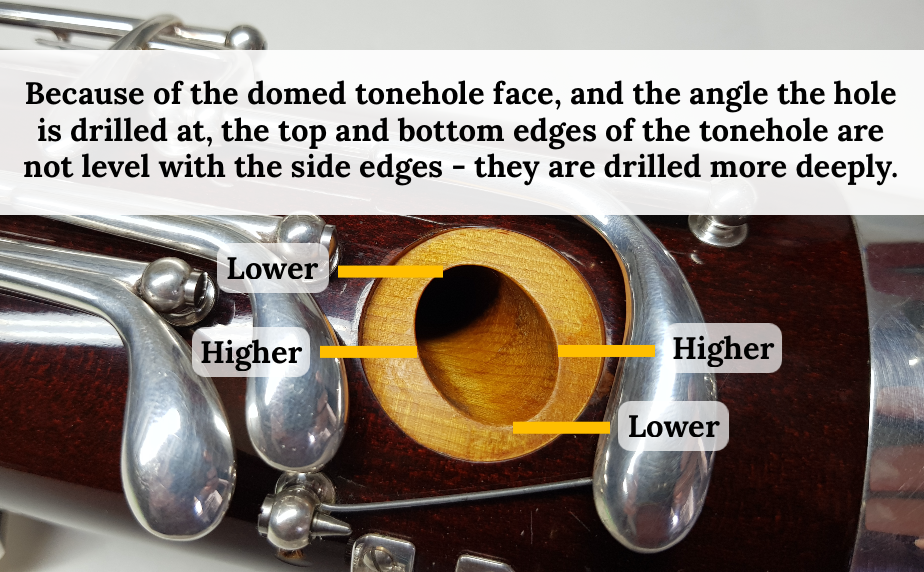

Complications arise, however, when you drill toneholes into a domed tonehole face at an oblique angle - as is the case with most of the toneholes on the bassoon. When this is done the tonehole rim becomes ovoid with edges that are not level. The picture below shows an example of this where the east and west edges are higher than the north and south ones. This reality is further complicated by the fact that the outside body of the bassoon is more asymmetrical than most other woodwinds.

Photograph: An angled tonehole drilled into the domed tonehole face of a bassoon

Angled toneholes like this cannot be successfully sealed with a flat pad. They require pads which conform to the same shape, or else the pad would not cover the whole of the rim, and would leak.

The solution? Domed pads. But, therein lies one of the major difficulties with re-padding a bassoon. Aside from the fact the pads are manufactured flat, and need to be adapted to fit the contours of the tonehole faces, every side of the pad needs to be carefully angled so that each part touches the tone hole at the same time. If the pad is even slightly askew, leaks can occur.

It is very time-consuming to get a perfect seal. The specialist bassoon repairer grows accustomed to the nuances of seating pads, using a feeler gauge to feel the pressure on every part of the closed pad, and making tiny adjustments to ensure every side exerts equal pressure. With around 25 pads to fit, this is a significant undertaking.

Some bassoon manufacturers flatten the tonehole faces to mitigate the difficulties involved with padding domed toneholes.

Photograph: A flattened tonehole face on a bassoon

4. The dreaded A and Bb

There are two tonholes on the bassoon which are notoriously difficult to pad correctly, the A and Bb. This is because a single pad has to cover more than one tonehole in a single tonehole face – seating a single domed pad over multiple toneholes, and achieving a perfect seal on each of them is a feat which takes experience and practice to accomplish. The task is further complicated by the fact that each of the toneholes needs to be sealed in its own right, and the repairer must know how to seat the pad so that no air can leak from one tonehole into another, or out of the sides of the pad itself.

Photograph: The Bb tonehole face on a bassoon, with three toneholes

5. Tonehole condition

Another major consideration when re-padding a bassoon is the condition of the tonehole faces themselves. Once a bassoon gets to the point at which most of the pads need changing, there will usually be some wear to the faces – the varnish sealant may have worn through, allowing air to leak through the wood itself which is surprisingly porous. As it wears the varnish can chip, causing gaps where leaks can occur, and the unvarnished wood grain can become rough, causing the surface to be too uneven to maintain a seal when a new pad is fitted.

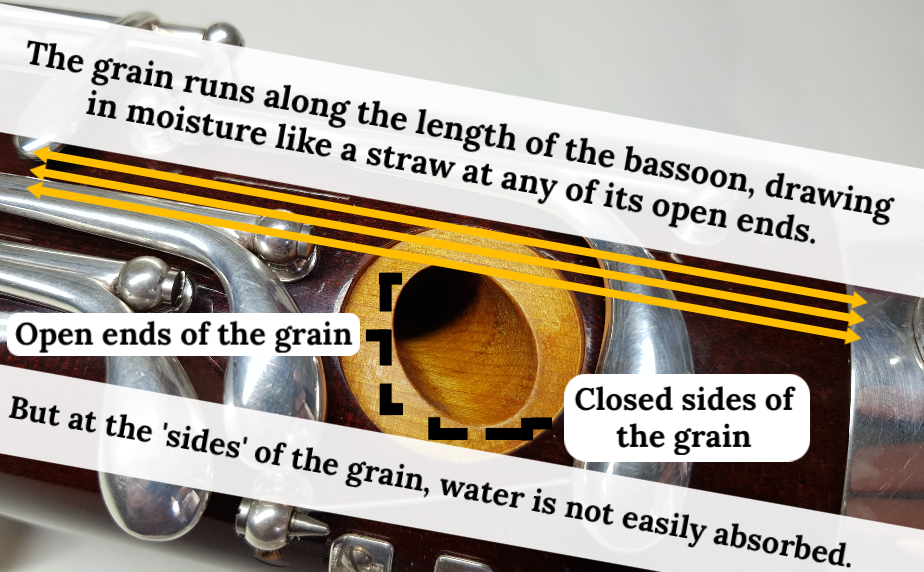

Bassoon toneholes are fairly unique compared to other wind instruments, because the maple wood bassoons are made from is particularly susceptible to water damage (the oboe, for example, is made from grenadilla wood, which does not easily absorb water). Over time, the moisture produced when playing the bassoon will cause the toneholes to swell and become misshapen, leading to leaks from the pad, and if left untreated, more serious damage to the instrument itself. The east and west tonehole edges are particularly susceptible, because the grain of the wood runs along the length of the instrument. The east and west edges of the toneholes are therefore on the ‘open’ edges of the end grain, where water is absorbed very easily – the north and south edges are cut into the ‘sides’ of the grain, where water doesn’t absorb very easily.

Photograph: A bassoon tonehole annotated to illustrate the direction of the wood grain

A specialist bassoon repairer will be able to scrape back the tonehole to its original dimensions, repair any damage, and re-seal it. In the worst cases we may even replace the tonehole face entirely. Trying to re-pad without fixing these issues is likely to result in leaks.

Bassoons which have been re-padded by general wind repairers, or repairers who don’t have specialist knowledge of how to fix these issues, can be damaged in the process, simply because techniques which may work on other instruments are not transferable to the bassoon.

Vacuum testing

A tight seal is one of the main goals we try to achieve when re-padding a bassoon, and continual vacuum testing is undertaken to check each of the pads. At Double Reed we use a combination of oral and mechanical tests to check the seal. Mechanical pressure testing with equipment such as a magnehelic gauge is particularly useful during the coronavirus pandemic, as it allows us to conduct vacuum tests on bassoons without putting our lips to the instrument.

If any of the elements of the re-pad are executed poorly, the bassoon may end up with tuning and intonation issues, an inferior tone, and notes which don’t speak easily when played. For this reason, it is important to always take your bassoon to a technician who specialises in bassoons, as many of the techniques used on other woodwind instruments are not transferable, and the bassoon takes special insight in order to re-pad correctly.

Summary

Five reasons why padding a bassoon is so complicated:

- Unusually complex, interconnected keywork

- Pads, corks and felts need to be precisely balanced to achieve both the right note, and a perfect seal

- Toneholes drilled at angles cause complications for fitting pads

- The dreaded A and Bb have multiple tone hole faces under one pad

- Poor tonehole condition prevents successful re-padding, even if all other steps are done correctly

Does your bassoon need a re-pad? Contact us for specialist advice and we will be happy to discuss your needs.

Article Author: Oliver Ludlow, In-House-Bassoon Specialist and Director at Double Reed Ltd.